kōlam

In 2018 I began to draw publicly, in order to free my imagery from the confines of gallery spaces and make it more accessible. It worked. My artwork began drawing the attention of people who otherwise had no interactions with fine art, especially children. Using an ephemeral medium in true mandala fashion, I began smearing chalk over the sidewalks of the quaint town that became my escape from the concrete jungle. I let my audience experience both admiration and a feeling of regret. They were roped into witnessing the loss of something they admired; the chalk faded away with countless footsteps and raindrops.

It became more convenient get up early and lay down an image before the town awoke, when the air was still fresh to breathe, leaving me the entire day to devote to other tasks. I worked under the gaze of a handful of early-risers enjoying their first cup of coffee under the tender morning sun.

Unknowingly, I had tapped into the longest tradition of art made by women, the kōlam. Practiced for centuries in India, the kōlam is made by drizzling rice flour on the sidewalk outside shops and homes, always in symmetrical geometric designs. The kōlam are visual prayers, and are walked over all day every day, and gone by day’s end. Much like them, my chalk drawings celebrate both the act of sharing a gift freely with everyone and the ephemeral nature of beauty, no matter how hard we may try to preserve it. In the east, art is not just for looking at – art is intended to do something. Have a daily practice. With internal purpose. I sought that purpose in my work.

Egg Tempera

I’ll chalk up my knack for exotic techniques to overeducation. I am one of the few art nerds in the world that still mix their own paint, instead of purchasing the ubiquitous art-store paint-tube. I also know my pigments by name.The declining quality of commercialized paints helped further that cause.

Egg tempera is a technique I fondly resort to, incorporating pigments that are no longer on the market – such as real lapis lazuli or madder lake – together with the water-soluble lipids of egg yolk emulsion. It’s a technique I’ve studied extensively and perfected over the course of nearly two decades. Of course the craft has been practiced for millenia.

I delight particularly in placing history side-by-side with innovation. Several of my works mingle egg tempera with gold point, gel pens and fluorescent inks. Often I juxtapose painted surfaces with color fields of various cross-hatched hues.

Discovery

A hundred year old book. Found on a leisurely bookstore browse. Looking for nothing in particular. Our customary way to pass a sunny spring weekend, among piles of old volumes. In the narrow Upper West Side store, two newly-weds holding hands could barely squeeze through. That’s what sparked the first light.

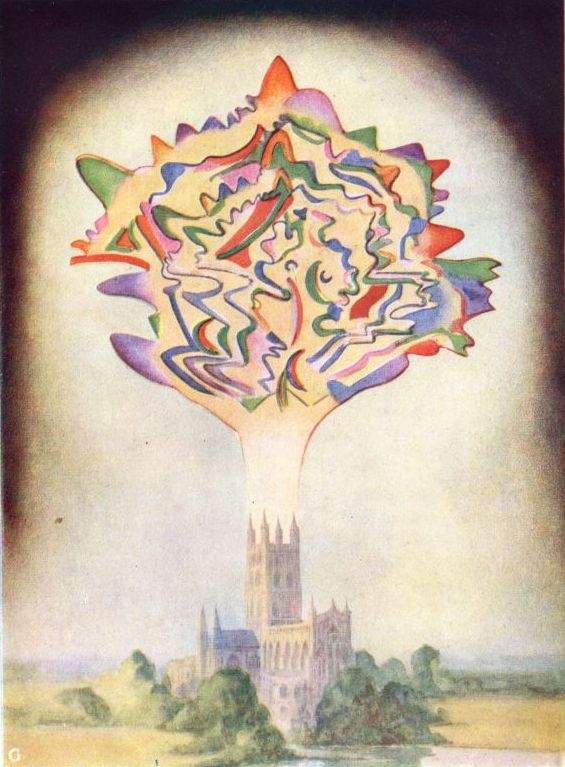

Amongst yellowed lithographs, drawings by Leadbeater, Besant and their cohorts, lay surprisingly… a Kandinski. But not an actual Kandinski, a drawing set in print 8 years before Mr. K. created his first abstract painting, representing… a musical performance blooming above the steeple of a gothic Church in the English Countryside.

The excitement of discovery mixed bitterly with a hint of betrayal; I knew Kandinski used to name his creations by the conventions of musical compositions.

The implications were tremendous if the celebrated artist ever laid eyes on this book.

He did.

Everything I knew about art history started to peel away.

In the thick atmosphere of turn-of-the-century salons and cafes, where the fumes of tobacco and still uncharted Amazonian narcotics mingled carelessly, the Modernist movement took shape not by the interference of imported artifacts, nor by the aesthetic invention of artistic genius, but by mere imitation of the observations of clairvoyants.

And if clairvoyance is to be dismissed as fantasy, then the illustrators of the century-old volume I held in my hand would have to be hailed as the greatest artistic innovators of the western world.

I had no interest in abstract art prior to that discovery. The aesthetic understanding that filtered through a standard arts education was a bore. But here I discovered that the roots of abstraction were not at all aesthetic.

For a decade after completing my BFA, I hadn’t created anything, feeling that everything I’d been taught was either superfluous or obsolete. Here was the answer.

I returned to childhood habits of drawing repetitive patterns, habits whose purpose I now fully understood. They helped me focus, automate and alter the way I streamed my thoughts and perceived my environment. Nature and science provided the source material.

I began to look at harmonies of color and proportion as a means to empower human beings. Artists had been doing it for centuries. Art education and critique focused solely on formal elements: composition, line, color… I began to use those same aesthetic elements to make paintings that could alter the atmosphere of an environment in a marked way, the way music does. Complete strangers who saw my work have walked up to me to remark that it worked.